As of July 20, 2012, this montage will no longer be available on Pod-O-Matic. It can be heard or downloaded from the Internet Archive at the following address / A compter du 20 juillet 2012, ce montage ne sera plus disponible en baladodiffusion Pod-O-Matic. Il peut être téléchargé ou entendu au site Internet Archive à l'adresse suivante:

http://archive.org/details/TheFibonacciSequence

pcast059 Playlist

=====================================================================

English Commentary – le commentaire français suit

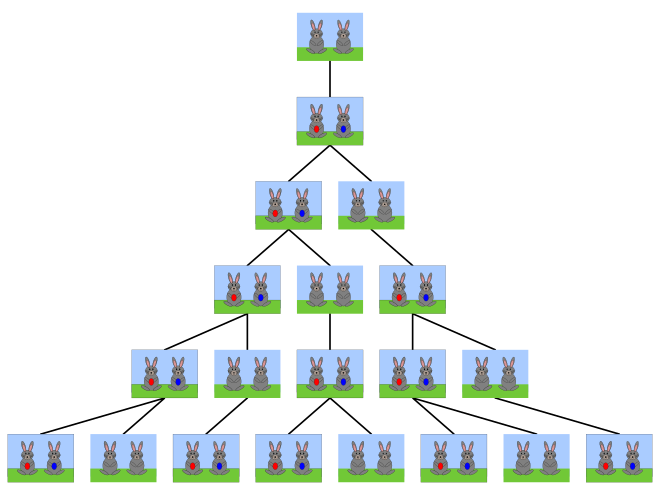

In the book Liber Abaci (Translation: The Book of Calculation, published in 1202), the author considers the growth of an idealized (biologically unrealistic) rabbit population:

A newly born pair of rabbits, one male, one female, are put in a field; rabbits are able to mate at the age of one month so that at the end of its second month a female can produce another pair of rabbits; rabbits never die and a mating pair always produces one new pair (one male, one female) every month from the second month on.

How many pairs will there be in one year?

The author of the book, Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci, thus presents the first documented example of what has come to be known as the Fibonacci sequence, that is the number of pairs of rabbits after each month:

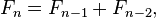

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, .., each number being derived as the sum of the two preceeding entries in the sequence, or

Fibonacci may have been the first western mathematician to have brought up the sequence, but the development of the Fibonacci sequence is attributed in part to Eastern mathematicians: Pingala (200 BC), Virahanka (c. 700 AD), Gopāla (c. 1135), and Hemachandra (c. 1150).

Some of you may remember the sequence being part of the at times twisted plot in the Dan Brown novel (and the Ron Howard motion picture) The DaVinci Code. Or this parody...

To illuistrate the sequence in the context of our “Music by the Numbers” montages, I will rely on a major work - the op. 1 caprices for solo violin by Paganini in the reference mono recording by Ruggiero Ricci. The entire recording is availabvle at:

http://archive.org/details/RuggieroRicci-PaganiniCaprices

The number “0” is represented by a movement from Bruckner’s Symphony no. 0 - Die Nullte (translated to The Zeroth, not to be confused with his symphony “00”, or his Studiensymphonie). The remainder of the sequence is illustrated by two feature works.

Czech composer Antonin Dvořák – a favourite of this blog – was a prolific chamber music composer. Over a period of almost 30 years, Dvořák's output of chamber music consists of more than 40 works for ensembles with strings, including at least 14 string quartets, as well as a number of works for quartet that don’t follow the usual pattern (thinking here of theCypřiše (or Cypresses).

Though his most famous quartet may very well be his American (his op. 96), this charming op. 34 pre-dates his American stay by 15 years. Dvořák was a champion of folk music, and this quartet has all the charm and earmarks of what made him successful with audiences.

Edvard Grieg composed nearly two hours of music for Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt (Grieg’s op. 23) , most of which is worth listening to in context of the play. However, rightly or wrongly, the Peer Gynt music is most often heard in the form of the two concert suites Grieg assembled (his opp. 46 and 55). Where the first suite contains some of the most famous and enduring passages of the incidental music (the Morning Mood and the Hall of the Mountain King), the second suite has more the feel of being a set of Grieg’s favourites – and the song that Solveig sings in Act 4 of the play is hauntingly beautiful. The suite provides only the instrumental backdrop – the French commentary embeds the song with soprano Lucia Popp.

I think you will love this music too.

=====================================================================

Commentaire français« Un homme met un couple de lapins dans un lieu isolé de tous les côtés par un mur. Combien de couples obtient-on en un an si chaque couple engendre tous les mois un nouveau couple à compter du troisième mois de son existence ? »

Ce problème est à l'origine de la suite de Fibonacci dont le n-ième terme correspond au nombre de paires de lapins au n-ème mois (voir le diagramme intégré au commentaire anglais_.

Fibonacci donne son nom à la suite d’entiers principalement car il fut le premier mathématicien occidental à la documenter. Toutefois, un bon nombre de mathématiciens Indiens ont abordé la même séquence numérique: Pingala (200 av. J-C), Virahanka (c. 700 ap. J-C), Gopāla (c. 1135), and Hemachandra (c. 1150).

Afin d’illustrer la suite, j’ai opté principalement pour des sélections de l’op. 1 de Nicolo Paganini, sa collection de caprices pour violon seul. L’enregistrement MONO du violoniste Ruggiero Ricci est la source de ces extraits – l’opus au complet fut téléchargé originalement à partir du site Public Domain Classic, et peut être téléchargé ici . Voici l’intégrale :

Le premier élément de la suite (le zéro) est illustré par un mouvement de la symphonie Die Nullte (ou no. 0) de Bruckner – à ne pas confondre avec sa Studiensymphonie, no. 00).

Un compositeur auquel je fauis souvent appel dans mes montages est le Tchèque

Antonin Dvořák. Comme compositeuir de musique de chambre, il fut des plus prolifiques, et compte une quinzaine d’oeuvres pour quatuor à cordes, don’t la majorité suivent la formule habituelle des quatre mouvements. Son quatuor op. 96 (le quatuor dit Américain, ou parfois appelé le drapeau Américain) est sans doute un de ses quatuors les plus joués, faisant la démonstration d’un des stratagèmes préférés du compositeur : l’usage de thèmes folkloriques. Le quatuor choisi aujourd’hui – son neuvième, op. 34, est un autre bel exemple de ces trucs.

Une des compositions les plus célèbres du Norvégien Edvard Grieg fut la musique qu’il composa pour accompagner la pièce d’Ibsen Peer Gynt. Des deux heures de muysique qui forment son op. 23, Grieg tira deux suites d’extraits (ses opp. 46 et 55). Pour le meilleur ou pour le pire, c’est dans cette forme que la majorité des mélomanes fuirent exposés à cette musique – hors du contexte de la pièce et faisant uniquement appel à l’orchestre, privant l’auditoire des passages choraux et des chansons conçues pour la scène. Si la première suite de Grieg contient les moments les plus adulés de la musique de scène (comme l’antre du Roi des Montagnes) , la deuième comprebd des titres qui (je suppose) sont des préférées du compositeur. En particulier, la chandon de Solveig (du quatrième acte) est particulièrement touchante – mais gagne plus de « punch » quand chantée – comme c’est le cas ici par Lucia Popp:

Bonne écoute!

No comments:

Post a Comment