AS we do at this time every year, let me take a moment to reflect on this past year, the year to come and share my collage YouTube playlist for the year 2017.

2017 Highlights

This was a "stay the course" year for us, with 31 new podcasts (including a few "quarterly podcasts" offered on Tuesdays. We introduced a new series on the Tuesday Blog (Cover 2 Cover) and completed the first set of 122 Listener Guides on our Project 366.

We maintained our bi-weekly presence on TalkClassical but failed to do much on OperaLively this year. No time!

Watch for 2018

As we continue at our monthly pace on Project 366, our Tuesday sjares and Friday Blogs will continue to "feed" our ongoing set of Listener Guides in the "Tine Capsule" series.

I hope to post a few times this year on OperaLively, but don't expect our frequency there (and everywhere else) to change much for the first half of 2018.

Don't be surprised if I start slowing things down a bit in the latter half of 2018 - and certainly in 2019. We have some important projects at home in the next year or two, and my musical activities may have to take a back seat. I hope to have all that behind me by 2020. Stay tuned!

Lastly, thanks to all my readers and followers on my many platforms - including Twitter. I always look forward to hearing from all of you.

Happy New Year 2018!

Friday, December 29, 2017

Tuesday, December 26, 2017

Beethoven Live!

|

| This is my post from this week's Tuesday Blog. |

For my final Tuesday Blog for 2017, as promised, here are some year-end fireworks from Mr. Beethoven: two symphonies that were created almost 210 years ago, on the fateful evening of 22 December 1808 - his Symphonies no. 5 and 6, performed in front of a captive audience and captured for posterity.

The first performance is from a radio broadcast of 23 May 1954, the last year of Furtwangler's life with the Berlin Philharmonic. The Pastorale is very slow, ruminative, moving to a different and more bucolic pace with a lingering, sweet quality, almost as though Furtwangler were losing himself in Beethoven's countryside for the last time.

In 1950 Victor de Sabata was temporarily detained at Ellis Island along with several other Europeans under the newly passed McCarran Act (the reason was his work in Italy during Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime). In March 1950 and March 1951 de Sabata conducted the New York Philharmonic in a series of concerts in Carnegie Hall, many of which were preserved from radio transcriptions to form some of the most valuable items in his recorded legacy. From these concets, we are featuring his stirring rendition of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

Both performances are enhanced by the energy provided by the audience - don't you think?

Happy listening!

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 6 in F Major, op. 68 ('Pastoral')

Berliner Philharmoniker

Wilhelm Furtwangler, conducting

(Live, 23 May 1954)

https://www.liberliber.it/online/aut...-68-pastorale/

Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, op. 67

New York Philharmonic

Victor de Sabata, conducting

(Live, 19 March, 1950)

https://www.liberliber.it/online/aut...-minore-op-67/

Friday, December 22, 2017

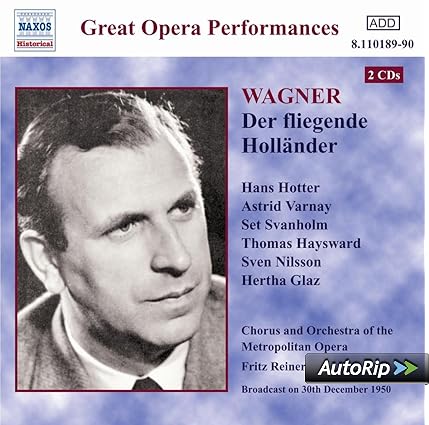

Der fliegende Holländer (Wagner)

|

| This is my post from this week's Once or Twice a Fortnight. |

I haven't been posting muchrecently - more like once or twice a quarter... Time is simply not on my side, but as I have a few days off work for the Holidays, I thought I'd finally get around to sharing this performance I downloaded a few years ago off the now defunct web site Public Domain Classic.

Let me (shamelessly) borrow from Paul Campion's fine notes for the NAXOS re-issue of this classic Met performance:

The tempestuous opening bars of the overture to Der fliegende Holländer throw us immediately into the passionate story of love, anguish and self-sacrifice that is to be played out in this, the first opera of Wagner’s musical maturity. Der fliegende Holländer was first performed on 2nd January 1843 at the Königliches Sächsisches Hoftheater in Dresden.

His initial conception was to present Der fliegende Holländer in one unbroken act, but shortly before the opening he reworked this into three separate acts, in which form it was customarily produced during the nineteenth century. (More recently, many directors and conductors have returned to Wagner’s first ideas and given the opera without any break; both are now regularly produced).

Among Wagner’s stage works, Der fliegende Holländer is the first great bridge between the Romantic operas of Weber, of whom he was an avid admirer, and his own Music Dramas, notably Tristan und Isolde and Der Ring des Nibelungen. Tellingly, it reveals his developing use of the leitmotif, which would be so significant in the creation of those later works. The most potent leitmotif, which returns repeatedly during the overture, is that of the Dutchman himself, who is fated to sail the seas until redeemed by the love of a faithful woman. Senta will herself make that sacrifice, and she relates the Dutchman’s haunting tale in her great second act ballad; at the climax of the third act she throws herself into the sea, finally to be seen embracing the Dutchman as his ship sinks beneath the merciless waves.

ABOUT THIS RECORDING

The 1950 production, at a later performance of which this recording was made, opened on the second night of Rudolf Bing’s first season as the Met’s general manager and was the occasion of two notable house débuts, those of Hotter and Nilsson, and two rôle débuts there, those of Varnay and Svanholm.

Hans Hotter was the supreme Wagnerian bass-baritone of his generation, and also sang rôles by Mozart, Mussorgsky and Verdi. Born in Offenbach am Main in 1909, he studied in Munich, giving his first concert there in 1929. After his 1930 operatic début in Troppau, he sang in Prague, Hamburg and, most famously, Munich, where he remained for 35 years. Hotter appeared in two Strauss premières, Friedenstag in 1938, and Capriccio in 1942, the year he also first sang in Salzburg. In 1947 he was at Covent Garden with the Wiener Staatsoper, returning for eighteen seasons singing rôles including Wotan and Hans Sachs; Hotter appeared at the Met from 1950 to 1954 and first sang at Bayreuth in 1952. Long accomplished also as a lieder singer, he has more recently participated in performances of Lulu and Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder with continuing success.

Astrid Varnay was born in Stockholm in 1918; at an early age she moved with her parents to the United States, where she later studied singing. Varnay sang at Brooklyn Academy in 1937, but her sensational first Metropolitan performance, as Sieglinde (Naxos 8.110058-60), was in 1941; she appeared there during nineteen seasons, principally in Wagnerian rôles, including six performances as Senta. Varnay later sang in Chicago, San Francisco and South America and appeared in sixteen consecutive Bayreuth seasons, where she was Senta in 1955-6 and 1959. Varnay first sang at Covent Garden in 1948 and thereafter in many European cities, including Florence, Paris, Vienna and Milan; considered the most dramatically intense Isolde and Brünnhilde of her generation, she was a fine Lady Macbeth, Elektra, Marschallin and, later, Klytemnestra. In retirement Varnay moved to Munich, where she still lives.

Born in Västerås, Sweden in 1904, Set Svanholm originally trained as an organist and made his baritone début at the age of 25; his début as a tenor was in 1936, as Radames in Aïda, but he excelled in Wagner, particularly as Lohengrin, Parsifal, Siegmund and Tristan. Appearances in London, Salzburg, Berlin, Vienna, Bayreuth and La Scala preceded Svanholm’s 1946 début at the Met, where he sang for ten seasons; he appeared at Covent Garden from 1948 until 1957, displaying his robust, focused tenor to superb effect. In 1956 Svanholm was appointed director of the Royal Opera in Stockholm; he died in Sweden in 1964.

Sven Nilsson, too, was born in Sweden, in 1898; he studied in Stockholm, making his operatic début in 1930. As member of the Dresden Staatsoper (1930-1944), he sang at Covent Garden in 1936 and in the première of Strauss’s Daphne in 1938; he also appeared in Amsterdam, Brussels, Milan and Drottningholm. In 1946 Nilsson returned to Stockholm, singing there until his death in 1970. Nilsson assumed principally Wagnerian rôles, notably Daland, which he performed during his only Met season, Pogner and Gurnemanz; and also Sarastro, Osmin and Ochs.

Fritz Reiner, born in Budapest in 1888, studied under Bartók. He was Dresden Staatsoper’s musical director from 1914 to 1922, subsequently taking charge of the Cincinnati Symphony. From 1931 Reiner taught at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and was Director of the Pittsburgh Symphony from 1938 to 1948, scheduling performances at Covent Garden, La Scala, Vienna and South America into his energetic career. He later conducted at the Met and in Chicago, remembered for his wide musical interests, but principally for interpretations of the Romantics, Wagner, Strauss and twentieth century composers. Reiner died in New York in 1963.

The recording is very good, though it does show the technical limitations of recording live performances in those days.

Happy listening!

Richard WAGNER (1813 - 1883)

Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), WWV 63

A Romantische Oper in three acts, with German libretto by the composer

PRINCIIPAL CAST

Der Holländer: Hans Hotter

Senta: Astrid Varnay

Erik: Set Svanholm

Daland: Sven Nilsson

Mary: Hertha Glaz

Der Steuermann Dalands: Thomas Hayward

New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus

New York Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

Fritz Reiner, conducting

Live performance, 30 December 1950

(Downloaded from Public Domain Classic, 2014)

Synopsis and Libretto - http://www.opera-arias.com/wagner/de...oll%C3%A4nder/

Details - https://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item...de=8.110189-90

Rudolf Serkin plays Beethoven

| No. 267 of the ongoing ITYWLTMT series of audio montages can be found in our archives at https://archive.org/details/pcast267 |

=====================================================================

Today's podcast and our upcoming Boxing Day Tuesday Blog will feature three major works by Beethoven he conducted at a monumental concert held on this day, almost 210 years ago. According to what we know of that evening's program, the last piece before intermission was the public premiere of his Piano Concerto no. 4.

The actual premiere took place almost 18 months earlier, at a private concert of the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz. The Coriolan Overture and the Fourth Symphony were premiered in that same concert.Beethoven dedicated the concerto to his friend, student, and patron, the Archduke Rudolph.

A review in the May 1809 edition of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung states that "[this concerto] is the most admirable, singular, artistic and complex Beethoven concerto ever". However, after its first performance, the piece was neglected until 1836, when it was revived by Felix Mendelssohn. Today, the work is widely performed and recorded, and is considered to be one of the central works of the piano concerto literature.

What is unique about this concerto is that, unlike other ones by Beethoven, the introduction is given to the soloist, not the orchestra. Also, its rondo finale is most joyous.

Today's soloist, Rudolf Serkin, is what we call in Frech "une valeur sûre", a trusted hand at the wheel when it comes to the great classical and romantic keyboard repertoire.

To open the podcast, I chose a recording by Serkin of the Hammerklavier sonata (more exactly the Große Sonate für das Hammerklavier). Hammerklavier literally means "hammer-keyboard", and is still today the German name for the fortepiano, the predecessor of the modern pianoforte.

The sonata's name comes from Beethoven's later practice of using German rather than Italian words for musical terminology, thus the sonata is his "Grand sonata for the fortepiano". "Hammerklavier" was part of the title to specify that the work was not to be played on the harpsichord, an instrument that was still very much in evidence in the early 1800s.

The work also makes extensive use of the una corda (or soft) pedal, with Beethoven giving for his time unusually detailed instructions when to use it. On a grand piano this pedal shifts the whole action including the keyboard slightly to the right, so that hammers which normally strike all three of the strings for a note strike only two of them.

The Hammerklavier stands out for its length (performances typically take about 45 to 50 minutes). While orchestral works such as symphonies and concerti had often contained movements of 15 or even 20 minutes for many years, few single movements in solo literature had a span such as the Hammerklavier's Adagio sostenuto. Its technical challenges and length make it one of the most demanding solo works in the classical piano repertoire.

I think you will love this music too!

Sunday, December 17, 2017

Project 366 - Bach Gets my GOAT

|

| Project 366 continues in 2017-18 with "Time capsules through the Musical Eras - A Continued journey through the Western Classical Music Repertoire". Read more here. |

Baseball fans will argue until they are blue in the face about everything and anything. Was this player “Safe” or “Our”? Was that ball “Fair” or “Foul”? Who was the better pitcher: Steve Carlton or Tom Seaver?

Everybody has their GOAT - “Greatest of All Time”. Honus Wagner? Ty Cobb? Babe Ruth? Is that before or after the Colour Barrier was broken? Was that before or after games were played at night? Do “Steroid era” players get considered?

To me, the GOAT was Willie Mays. He could do everything – he could hit, he could run, he could play the field… Everybody remembers that catch at the Polo Grounds during Game 1 of the 1954 World Series. I wasn’t born yet, but I saw the footage. Nobody will ever remember Vic Wertz – the guy who thought he hit it out of Mays’ reach – but he’s viewed today as a goat of a different kind…

Baseball fans aren’t the only ones to debate things, as we humanoids are an argumentative bunch! The GOAT argument is something that transcends baseball and gets into every human endeavor, and the parameters that make somebody ”great” are always open to interpretation.

Although it may not be a fair question to ask, who is – in your mind – the GOAT among Classical Music luminaries – composers, performers…

Not easy…

The reason why it isn’t easy is because the playing field isn’t level. Going back to baseball for a minute, the game has evolved a lot over 100-plus years, athletes are bigger and stronger, the parameters of play have changed – whether the pitcher’s mound was at this or that height, whether seasons had this many or that many games, whether or not teams travelled from coast to coast. I mean, it’s hard to come up with ways of compensating for these factors when players played under different conditions.

I will readily admit that my heart has swung over the years, and I have to cop out and grant the title to two composers, one of which is featured with some time capsules n today's installment.

Johann Sebastian BACH (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer and organist. The most important member of the Bach family, his

genius combined outstanding performing musicianship with supreme creative

powers in which forceful and original inventiveness, technical mastery and

intellectual control are perfectly balanced. While it was in the former

capacity, as a keyboard virtuoso, that in his lifetime he acquired an almost

legendary fame, it is the latter virtues and accomplishments as a composer that

by the end of the 18th century earned him a unique historical position.

His musical language was distinctive and extraordinarily

varied, drawing together and surmounting the techniques, the styles and the

general achievements of his own and earlier generations and leading on to new

perspectives which later ages have received and understood in a great variety

of ways.

The Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV; lit.

Bach-Works-Catalogue) is a catalogue of compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach

first published in 1950, edited by Wolfgang Schmieder. 1126 compositions were assigned a BWV number in the 20th

century. More compositions were added to the catalogue in the 21st century. The

Anhang (Anh.; Annex) of the BWV lists over 200 lost, doubtful and

spurious compositions. I have selected time capsules that exemplify specific portions of the catalogue.

Works List - http://www.jsbach.net/catalog/index.html

- 1-524 - Vocal Works (Cantatas, motets, masses and other sung works, both secular and sacred.)

Listener Guide #134 and 135 - Mass in B Minor. It has been suggested that Bach intended the completed Mass in B minor for performance at the dedication of the new Hofkirche in Dresden, which was begun in 1738 and was nearing completion by the late 1740s. However, the building was not completed until 1751, and Bach's death in July, 1750 prevented his Mass from being submitted for use at the dedication; the first documented complete performance took place in 1859. (Once Upon the Internet #45 - March 8, 2016)

-

L/G 134 - (Kyrie & Gloria)

L/G 135 - (Credo, Sanctur, Agnus Dei)

- 525-771 · Organ Works

Listener Guide #136 - J.S. Bach "en España". Organist Michael Reckling, who frequented the Church of Our Lady of the Incarnation of Marbella was impressed with the location’s acoustics, and he took upon himself to engage Monsignor Rodrigo Bocanegra (at that time pastor of the Church) in 1970 to support this initiative. The ambitious project would yield the first large tracker organ and one of the most important instruments built in Spain in the 20th Century: the Organo Del Sol Mayor. The fine construction was carried out between 1971 and 1975 by the master organ builders Gabriel Blancafort and Joan Capella from Collbató, at their workshop near Barcelona. (Once Upon the Internet #35 - March 17, 2015)

(Also, Listener Guide #8)

- 772-994 - Keyboard Works

Listener Guide #137 and 138 - Das Wohltemperierte Klavier (Book I). Composed about 20 years apart, the two sets of 24 preludes and Fugues that constitute the two books of Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier didn’t start off as one huge collection of 48 works – in fact, the set of “24 Preludes and Fugues” composed in 1742 were not issued as a “sequel” to the original WTC of 1722. Musicologists have, however, come to combine the two sets, as they are both in the same mould – exploiting the concept that many more composers (from Chopin to moist recently François Dompierre) have followed, that of creating a set of works written in every major and minor key.Featured today is the fist book of 24 preludes and fugues. I propose you consider the first 12 as L/G 137, and the last 12 as L/G 138.(Once Upon the Internet #18 - October 13, 2013)

- 995-1040 - Chamber and Solo Instrumental Works (includes duos, trios and works for solo lutem violin, cello and flute)

Listener Guide #139 - Three Bach Cello Suites Bach's cello suites stand out because of the paradox they represent; they are simple yet complex, they achieve the effect of implied three- to four-voice contrapuntal and polyphonic music in a single musical line. As formulaic compositions, they follow the usual Baroque musical suite make-up, each movement based around a baroque dance type. The cello suites are structured in six movements each: prelude, allemande, courante, sarabande, two minuets or two bourrées or two gavottes, and a final gigue. (Once Upon the Internet #51 - October 18, 2016)

(Also, Listener Guide #96 and 114)

(Also, Listener Guide #96 and 114)

Listener Guide #140 - J.S. Bach Violin Concertos. Bach’s violin concertos are quite few – there are the three recognized concertos (BWV 1041, 1042 and 1043), a “triple concerto” (for violin, flute and harpsichord), and a host of reconstructed or fragmentary works. Our montage dips into both the “straight up” and the “reconstructed” concertos.

Listener Guide #141 - Edwin Fischer (1886 -1960) Edwin Fischer was the first pianist to make a complete recording of Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier which he commenced in 1933. Perhaps the best adumbration of Fischer’s musical outlook is his recording of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue recorded in 1931. Also featured are all the . The listener guide features his recording of three of concertos for keyboard with his Chamber Orchestra. (ITYWLTMT Montage #266 - December 8, 2017)

Listener Guide #142 and 143 - Brandenburg Perspectives. A showcase of six of Bach’s greatest orchestral works with some filler as a segue into perspective, about how certain interpretations and choices by the artists involved (or even by the composer himself) provide an at times curious insight on the term “flavour of the day”. (ITYWLTMT Montages Nos. 83 and 84 - December 2012)

L/G # 142 (Concertos 4 -6)

L/G 143 (Concertos 1-3)

Tuesday, December 12, 2017

Orchestre Symphonique De Montréal, Holst, Charles Dutoit – The Planets

|

| This is my post from this week's Tuesday Blog. |

For my last two Tuesday Blogs for 2017, I programmed some Christmas presents for you, works that should please everybody, casual and vested CM lovers alike.

Written between 1914-1916 by British composer Gustav Holst, this week’s featured work ‘The Planets’ is a suite of seven short tone poems, each representing one the known planets of the Solar System seen from Earth at the time, and their corresponding astrological character.

According to Kenric Taylor’s “Gustav Holst website” Holst seemed to consider The Planets a progression of life.

- "Mars" perhaps serves as a rocky and tormenting beginning. In fact, some have called this movement the most devastating piece of music ever written!

- "Venus" seems to provide an answer to "Mars," its title as "the bringer of peace," helps aid that claim.

- "Mercury" can be thought of as the messenger between our world and the other worlds.

- Perhaps "Jupiter" represents the "prime" of life, even with the overplayed central melody, which was later arranged to the words of "I vow to thee, my country."

- Through "Saturn" it can be said that old age is not always peaceful and happy. The movement may display the ongoing struggle for life against the odd supernatural forces.

- "Saturn" is followed by "Uranus, the Magician," a quirky scherzo displaying a robust musical climax before…

- … the tranquility of the female choir in "Neptune" enchants the audience.

(More insight on the astrological meaning of each planet can be found here )

The piece displays that Holst was in touch with his musical contemporaries. There are obvious ideas borrowed from Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Debussy (the quality of "Neptune" resembles earlier Debussy piano music.)

Holst never wrote another piece like The Planets again. He hated its popularity. When people would ask for his autograph, he gave them a typed sheet of paper that stated that he didn't give out autographs. The public seemed to demand of him more music like The Planets, and his later music seemed to disappoint them. In fact, after writing the piece, he swore off his belief in astrology, though until the end of his life he cast his friends horoscopes. How ironic that the piece that made his name famous throughout the world brought him the least joy in the end.

For your listening pleasure, I chose the 1987 Decca release by Charles Dutoit and l’Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal from my vinyl collection. Some of the movements were already available on YouTube, I simply added the missing movements to complete the playlist.

--David Hurwitz

Gustav HOLST (1874–1934)

The Planets, op. 32

Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal

Choeur des Femmes de l'OSM [”Neptune”] (Iwan Edwards, chorus master)

Charles Dutoit, conducting

London Records – 417 553-1 LH

Format: Vinyl, LP, Album (DDA)

Recording location: L'église de Saint-Eustache, Qc , June 1986.

YouTube Playlist - https://www.youtube.com/playlist?lis...HhUffUlNTwt8sl

Internet Archive URL - https://archive.org/details/05SaturnTheBringerOfOldAge

Friday, December 8, 2017

Edwin Fischer (1886 -1960)

| No. 266 of the ongoing ITYWLTMT series of audio montages can be found in our archives at https://archive.org/details/pcast266 |

=====================================================================

This week’s podcast features a pianist I find has been much

overlooked in recent years. Edwin Fischer (1886 –1960) was a Swiss classical

pianist and conductor who is regarded as one of the great interpreters of J.S.

Bach and Mozart of his generation, if not of the twentieth century.

Precocious, Edwin Fischer entered the Basle Conservatory at

age ten where he studied with the composer Hans Huber. When Fischer was

eighteen he moved to Berlin to study at the Stern Conservatory with Liszt pupil

Martin Krause (who would later teach Claudio Arrau).

After a period of teaching at the Stern Conservatory,

Fischer gave recitals and at this time appeared with such eminent conductors as

Willem Mengelberg, Arthur Nikisch, and Bruno Walter. He toured in Europe and

Britain, but gave only a limited number of concerts.

In 1931 Fischer succeeded Artur Schnabel as director of the

Berlin Hochschule für Musik, a post he held for four years. During World

War II Fischer returned to his native Switzerland from where he gave

master-classes for a number of later prominent pianists (such as Alfred

Brendel, Helena Sá e Costa, Mario Feninger, Paul Badura-Skoda and Daniel

Barenboim). He continued to tour until 1954 when he stopped performing in

public as he was suffering from a paralysis of his hands.

Fischer’s repertoire was dominated by Bach, Beethoven,

Mozart, and Schubert. He also played Chopin and Schumann, but had a wide

knowledge of the piano repertoire. Describing Fischer’s pianistic personality

is not easy. He was a genuinely honest and kind person whose humanity shone

through his music in performances that contained a beautiful, seamless legato,

and a pellucid tone quality that is unique to Fischer. He found all things

spiritual extremely important to his life as a musician, always searching for

the true inner spirit of the music he was interpreting.

Edwin Fischer was the first pianist to make a complete

recording of Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier which he commenced in

1933. Perhaps the best adumbration of Fischer’s musical outlook is his

recording of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue recorded in 1931. The Fantasy

sounds more like an improvisation with Fischer not fearing to double notes and

use extremes of dynamic, his pianissimo being almost hypnotic as it draws the

listener in. He makes this Fantasy into an improvisational poem, at times

creating moments of aching beauty. He brings the same qualities to Busoni’s

arrangement of Bach’s Chorale Ich ruf’zu dir.

In 1930 Fischer formed his own chamber orchestra of Berlin

musicians, which he conducted from the keyboard. In 1950 Fischer gave a series

of concerts in London and other European cities to commemorate the bicentenary

of Bach’s death. In these concerts he played all the concertos for keyboard.

Today’s podcast features his recording of three of these concerti with his

Chamber Orchestra.

I think you will love this music too.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Schubert: 15 Lieder / Gundula Janowitz, Charles Spencer

|

| This is my post from this week's Tuesday Blog. |

This week’s Tuesday Blog is an installment of our Cover2Cover series, with a 1989 recording of the esteemed soprano Gundula Janowitz in a Milan recital, singing a selection of 15 lieder by Franz Schubert, accompanied at the piano by Charles Spencer.

According to classical-music.com, Schubert's body of work includes over 600 songs for voice and piano. That number alone is vastly impressive - many composers fail to reach that number of compositions in their entire output, let alone in a single genre. But it isn't just the quantity that's remarkable: Schubert consistently, and frequently, wrote songs of such beauty and quality that composers such as Schumann, Wolf and Brahms all credited him with reinventing, invigorating and bringing greater seriousness to a previously dilletante musical form.

Maybe it’s just me, but I sense there’s a preponderance of male Schubert singers; Schubert's Winterreise is performed by both men and women. However, even when there are implied "characters," the tendency is inconsistent: as an example, Schubert's Die schöne Müllerin is almost always sung by men, while Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen is split almost equally between men's and women's voices in performance.

Gundula Janowitz officially retired from the stage in 1990 and, according to most accounts, gave occasional recitals until around the middle of that decade with her final recital –captured for posterity in a bootleg recording - in September 1999. As far as I know, there are only two mainstream recordings of Ms Janowitz singing Schubert (with the exception of that final recital), one for DGG (with Irwin Gage at the piano) and this late-career recital with Spencer at the piano re-issued on The Nuova Era and Brilliant Classics labels.

I agree with some of the contemporaneous reviews of this and her final recital a decade or so later; the singer is in remarkably fresh voice throughout. There’s a certain loss of bloom, inevitably, and an occasional brittleness of intonation, but the unique sound is unmistakable, the delivery still clear and confident.

Happy Listening!

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

- Der Winterabend D938, Text by Karl Gottried von Leiner

- Auf dem See D543, Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Das Lied im Grunen D917, Text by Fredrich Reil

- An die untergehende Sonne D457, Text by Ludwig Gotthard Theobul Kosegarten

- Der liebliche Stern D861, Text by Ernst Schulze

- An den Mond D296, Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Nachtstuck D672, Text by Johann Baptist Mayrhofer

- Augenlied D297, Text by Johann Baptist Mayrhofer

- Der blinde Knabe D833, Text by Jakob Nikolaus de Jachelutta Craigher

- Am Grabe Anselmos D504, Text by Matthis Claudius

- Bei Dir allein D866, Text by Johann Gabriel Seidl

- Die abgebluhte Linde D514, Text by Ludwig Graf von Savar-Felso Videk Szechenyi

- Fischerweise D881, Text by Franz Xaver Freiherr von Schlechta

- Geheimnis D491, Text by Johann Baptist Mayrhofer

- An die Musik D547, Text by Franz von Schober

Gundula Janowitz, soprano

Charles Spencer, piano

Live Milan, Italy, 1989

Nuova Era 6860 [http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/...bum_id=134490]

Internet Archive URL - https://archive.org/details/GundulaJanowitzFranzSchubert15Lieder

Video posted by Johnny BeGood

Friday, November 24, 2017

In Memoriam: Sir Jeffrey Tate (1943 - 2017)

| No. 265 of the ongoing ITYWLTMT series of audio montages can be found in our archives at https://archive.org/details/pcast265 |

=====================================================================

Earlier this year, I posted a Tuesday Blog saluting g

the career of conductor Sir Jeffrey Tate, who passed away this past June. This

week’s post is another tip of the hat to Sir Jeffrey, this time in three

symphonies by Joseph Haydn.

In 1985 Tate was appointed the first Principal Conductor of

the English Chamber Orchestra and began a major recording programme for EMI

which included the complete Mozart symphonies as well as a number of

Haydn's. Tate's Haydn and Mozart are in a class of their own. Using modern

instrumental forces and often adopting tempi which are much broader than we

have come to expect from period orchestras, Tate achieves a lightness and

lyricism which make every note compelling.

As we discussed in yet another Tuesday Blog earlier

this year, Haydn’s London symphonies can be categorized into two groups:

Symphonies Nos. 93–98, composed during Haydn's first visit to London, and

Symphonies Nos. 99–104, composed in Vienna and London for his second visit.

Today’s trio of symphonies date from the first set and were presented to London

audiences in a different order – they were his third, sixth and fourth.

Haydn's music contains many jokes, and the Surprise

Symphony (no. 94) includes probably the most famous of all: a sudden fortissimo

chord at the end of the otherwise piano opening theme in the variation-form

second movement. The music then returns to its original quiet dynamic, as if

nothing had happened, and the ensuing variations do not repeat the joke. (In

German it is commonly referred to as the Symphony mit dem Paukenschlag -

"with the kettledrum stroke").

The symphony no. 96 has been called the Miracle

symphony due to the story that, during its premiere, a chandelier fell from the

ceiling of the concert hall in which it was performed. The audience managed to

dodge the chandelier successfully as they had all crowded to the front for the

post-performance applause, and the symphony got its nickname from this. (More

careful and recent research suggests that this event actually took place during

the premiere of his Symphony No. 102).

Haydn was composing the Symphony no. 98 when he heard, and

was greatly distressed by, the news of Mozart's death. The Adagio,

solemn and hymn-like, makes noticeable use of material from two works by

Mozart, the Coronation Mass and Symphony No. 41

("Jupiter").

I think you will love this music too.

Sunday, November 19, 2017

Project 366 - Early Music Time Capsules

|

| Project 366 continues in 2017-18 with "Time capsules through the Musical Eras - A Continued journey through the Western Classical Music Repertoire". Read more here. |

According

to Wikipedia, Early

music refers to music, especially Western art music, composed prior to

the Classical era. The term generally comprises Medieval music

(500–1400) and Renaissance music (1400–1600). Whether it also

encompasses Baroque music (1600–1760) is a matter of opinion in some

learned circles. Further, the term has come to include "any music for

which a historically appropriate style of performance must be reconstructed on

the basis of surviving scores, treatises, instruments and other contemporary

evidence."

To begin

our set of time capsules, I thought I’d begin with a pair of listener guides

that illustrate Medieval and Renaissance Music:

Listener

Guide # 123 “Anonymous” - Anonymous works are works of art or literature, that have an

anonymous, undisclosed, or unknown creator or author. For the most part, works

attributed to Anonymus pre-date the Baroque era, and can be thought of as being

passed down following “oral” tradition (ITYWLTMT Montage #245

– 14 Apr. 2017)

Listener

Guide # 124 “Robert Johnson: Lute Music” - Robert Johnson was the son of lutenist to

Elizabeth I. Following the death of his father in 1594, Robert was taken under

the care of Lord Hunsdon, later Lord Chamberlain to Elizabeth and the patron of

the acting company later called The King’s Men of which Shakespeare was a

member. This created a strong artistic influence on Johnson, who went on to

write songs and music for this company including plays by Shakespeare, Beaumont

and Fletcher, and Webster. Johnson's main claim to fame is that he composed the

original settings for some of Shakespeare's lyrics, the best-known being

probably those from The Tempest. (Cover2Cover

#3 – 2 May 2017)

As general

examples of baroque music, let me suggest the following pair of additional

listener guides:

Listener

Guide # 125 “Helmut Walcha - Organ Masters Before Bach” – This Guide provides an overview

of compositions from the 16th to the 18th centuries that stands as a foundation

for Bach’s great organ music. Bach walked a long distance to meet Buxtehude,

and stayed with him for three months, absorbing much of his technique. Other

composers represented include such well known names as Johann Pachelbel and

Georg Böhm, as well as lesser known composers such as Nicolaus Bruhns, Samuel

Scheidt and Vincent Lübeck. (Cover2Cover

#2 – 4 April 2017)

Listener

Guide # 126 “Baroque Showcase” – Thius listener guide avoids the “usual suspects” – a few of whom we

will focus on later - and provides a modest sampling of compositions by other

baroque-era composers. (ITYWLTMT

Montage #241 – 24 Feb. 2017)

Johann

Sebastian Bach probably reigns supreme among Baroque composers – he will be the

subject of his own chapter in December. Two other names deserve significant

mention:

Antonio

Vivaldi (1678–1741)

Antonio Vivaldi was one of the most renowned figures in European baroque music. Born in Venice, Vivaldi was ordained as a priest though he instead chose to follow his passion for music. A prolific composer who created hundreds of works, he became renowned for his concertos in Baroque style, becoming a highly influential innovator in form and pattern. He was also known for his operas, including Argippo and Bajazet.

Full

Biography – http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Lib/Vivaldi.htm

Listener

Guide # 127 “Vivaldi – Trio Sonatas op. 1” – Vivaldi published a collection of twelve

trio sonatas (his opus one) in 1705. This edition has only partly survived;

today's performers rely on a reprint by Estienne Roger of Amsterdam which dates

from around 1715. (Cover2Cover

#4 – 26 Sept. 2017)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6077657-1410469904-8594.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6077657-1410469904-8594.jpeg.jpg)

Listener

Guide # 128 “Vivaldi - New Philharmonia Orchestra - Leopold Stokowski – Le

Quattro Stagioni” –

Perhaps the finest "big band" version of the Four Seasons comes from

this oft-reissued Phase 4 recording which brims with the conductor's

characteristic and highly personal tonal color, rescoring and inflection, but

it's deeply heartfelt and thoroughly delightful. (Vinyl’s

Revenge #11 #4 – 13 Oct. 2015)

George

Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

George Frideric Handel composed operas, oratorios and instrumentals. Handel was born in Halle, Germany, in 1685. In 1705 he made his debut as an opera composer with Almira. He produced several operas with the Royal Academy of Music in England before forming the New Royal Academy of Music in 1727. When Italian operas fell out of fashion, he started composing oratorios, including his most famous, Messiah [Listener Guides #50 and 51].

Full

Biography – http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Lib/Handel.htm

Handel’s

work catalog - http://www.musiqueorguequebec.ca/catal/handel/hangf.html

Listener

Guide # 129 “George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)” – A modest sampling of works by Handel,

including his music for the Royal Fireworks. (ITYWLTMT

Montage #244 – 31 Match 2017)

Listener

Guide # 130 “Shellac's Revenge” – The Handel organ concertos, composed in London between 1735 and 1751,

were written as interludes for performances of his oratorios. They were the

first works of their kind for organ with chamber orchestra accompaniment and

served as a model for later composers. (Once Upon the

Internet #56 – 28 Match 2017)

Listener Guides #131 – 133 – “Handel: Radamisto” - [Opera in three acts]

Joyce DiDonato (Radamisto), Maite Beaumont (Zenobia), Zachary Stains (Tiridate), Patrizia Ciofi (Polissena), Carlo Lepore (Farasmane), Il Complesso Barocco under Alan Curtis (Once or Twice a Fortnight - 11 Mar 2014)

Synopsis @ https://www.operalogg.com/radamisto-opera-av-georg-friedrich-handel-synopsis/

Libretto @ http://www.haendel.it/composizioni/l...pdf/hwv_12.pdf

Friday, November 17, 2017

Project 366 - Time capsules through the Musical Eras

For Part One of Project 366, click here.

Part Two - Time capsules through the Musical Eras

A Continued

journey through the Western Classical Music Repertoire

In Part One

of Project 366, we launched a comprehensive look at the Classical Music

repertoire through a series of thematic Listener Guides. So far, we have shared

122 of these, and launch in Part Two a second tranche of 122 guides following a

long arc that will take us to the end of 2018.

Part One

consisted of a series of chapters exploring different musical genres – from

solo instrumental music, to Grand Opera and everything in between. In Part Two,

we will start fresh, and intend to traverse the repertoire along a timeline

that will feature musical eras, musical traditions and some of the great

composers that marked these eras and traditions.

Layout

of Part Two

500 years

of Western Classical Music can be depicted along a simple timeline:

There are

four “great” classical music periods, which mirror the evolution of most art

forms. The choice of the dates shown on the timeline is somewhat arbitrary; the

dates 1600, 1750 and 1820 don’t represent anything specific or eventful as far

as I can see. I view those as guide posts – call them timeposts – that allow us to provide a periodic context, nothing

more. I will extend the Baroque to “the left” of the timeline by including

renaissance and ancient music along with baroque under an “Early Music” era.

Each of the

four main eras will be explored over several chapters, with a focus on four

“significant” transitional and transformational figures: Johann Sebastian Bach

(Early Music), Ludwig van Beethoven (classical), Peter Tchaikovsky (Romantic)

and Igor Stravinsky (Modern) who will get chapters exclusively dedicated to

them. We will meander more in the classical era, allowing us to showcase two of

its significant architects – Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – to get

significant airtime along with other contemporaries and pupils.

The final

caveat I want to leave you with is that, though we will progress along the

timeline methodically, I make no pretense to keep things in perfect

chronological order (sometimes, music from other eras may intrude into some

listener guides, for instance). I intend to keep to the spirit of this

time-based approach, but not to the letter!

| Early Music | |

| Ealy Music Time capsules | 123-133 |

| Bach Gets my GOAT | 134-143 |

| Haydn, Mozart and the Classical Period | |

| Postcards from the (Classical) Edge | 144-153 |

| Mozart Gets My GOAT too | 154-163 |

| Hooked on Haydn | 164-173 |

| Beethoven Floats my BOAT | 174-184 |

| The Romantics | |

| Les Romantiques | 185-194 |

| Die Romantiker | 195-208 |

| Midsummer Romantics Mashup | 209-217 |

| No more Romantiki than Tchaikovsky | 218-227 |

| The Moderns | |

| Modern Time Capsules | 228-237 |

| Stravinsky Time Capsules | 238-244 |

Tuesday, November 14, 2017

Rachmaninov on Vinyl

|

| This is my post from this week's Tuesday Blog. |

This week’s Vinyl’s Revenge considers two orchestral works by Sergey Rachmaninov, emanating from two different periods in his composing career.

Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2 was written in 1906–07. The score is dedicated to Sergei Taneyev, a Russian composer, teacher, theorist, author, and pupil of Tchaikovsky. Alongside his second and third Piano Concertos, this symphony remains one Rachmaninov's best known compositions.

Parts of the third movement were used for pop singer Eric Carmen's 1976 song, "Never Gonna Fall in Love Again", which borrowed the introduction and main melody of the third movement as the song's chorus and bridge, respectively. The melody was also used by jazz pianist Danilo Pérez as the main theme of his tune "If I Ever Forget You" on his 2008 album Across the Crystal Sea.

The premiere was conducted by the composer himself in Saint Petersburg on 8 February 1908. Today’s performance is by Lorin Maazel and the Berlin Philharmonic.

Completed in 1940, the Symphonic Dances are Rachmaninov’s last composition. The work is fully representative of the composer's later style with its curious, shifting harmonies, the almost Prokofiev-like grotesquerie of the outer movements and the focus on individual instrumental tone colors throughout (highlighted by his use of an alto saxophone in the opening dance).

The Dances are an exercise in nostalgia for the Russia he had known; the opening three-note motif, introduced quietly but soon reinforced by heavily staccato chords and responsible for much of the movement's rhythmic vitality, is reminiscent of the Queen of Shemakha's theme in Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Golden Cockerel, the only music by another composer that he had taken out of Russia with him in 1917.

They also effectively sum up his lifelong fascination with ecclesiastical chants. In the finale he quotes both the Dies Irae and the chant "Blessed be the Lord".

The version I retained – am old Melodiya recording by Evgenii Svetlaniv from the same ABC Classics reissue that contained Tchaikovsky’s Suite no. 4 shared earlier this year – has been posted on my YouTube channel for a while and (to my chagrin) misses the first few bars. I did remedy the situation by digging through my digital copies, and have rectified the situation in the Internet Archive (audio only) version.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3957302-1350489772-3094.jpeg.jpg)

Sergey RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Symphony No.2 in E Minor, Op.27

Berliner Philharmoniker

Lorin Maazel, conducting

Deutsche Grammophon -- 2532 102 (ADD, Released: 1983)

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?lis...j2MPR5iwPZ7VdL

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

USSR Symphony Orchestra

Yevgeny Svetlanov conducting

ABC Classics AY 67032 (AAA, Recorded 1973)

Internet Archive URL - https://archive.org/details/05RachmaninovSymphonicDancesFI

Friday, November 10, 2017

John Field (1782-1837)

| No. 264 of the ongoing ITYWLTMT series of audio montages can be found in our archives at https://archive.org/details/pcast264 |

=====================================================================

Before Liszt,

before Chopin, there was John Field, probably Ireland’s most

notable export before Guinness Stout. Field was very highly regarded by

his contemporaries and his playing and compositions influenced many major

composers, including Chopin, Liszt, Johannes Brahms and Robert

Schumann.

John Field

was born in Dublin into a musical family, and received his early education

there, in particular with the immigrant Tommaso Giordani. The Fields soon moved

to London, where Field studied under Muzio Clementi. Under his tutelage,

Field quickly became a famous and sought-after concert pianist. Together,

master and pupil visited Paris, Vienna, and St. Petersburg.

Ambiguity

surrounds Field's decision to remain in Russia from 1802 onwards, but it is

likely that Field acted as a sales representative for the Clementi Pianos.

Although little is known of Field in Russia, he undoubtedly contributed

substantially to concerts and teaching, and to the development of the Russian

piano school.

Field is

best known as the instigator of the nocturne – 18 in total plus associated

pieces such as Andante inedit, H 64. These works were some of the most

influential music of the early Romantic period: they do not adhere to a strict

formal scheme (such as the sonata form), and they create a mood without text or

programme. A handful of these open today’s podcast.

Similarly

influential were Field's early piano concertos, which occupy a central place in

the development of the genre in the 19th century. One interesting trait of his

piano concertos is their limited choice of keys: they all use either E-flat

major or C major at some point (or both, in the last concerto's case). Composers

such as Hummel, Kalkbrenner and Moscheles were influenced

by these works, which are particularly notable for their central movements,

frequently nocturne-like. I programmed his concerto no. 5 in today’s montage.

To close, I

included an homage to Field by his fellow Irish countryman Hamilton Harty.

Harty's career was mostly as a conductor, notably of the Halle Orchestra of

Manchester, during which time he made it one of the best orchestras in Europe,

and was part of the early rediscovery and promotion of Baroque music by

creating orchestrations of Handel's music that were popular until the Period

Instrument movement. Harty orchestrated some of Field's pieces to create a

"John Field Suite" to promote the composer who had been mostly

forgotten. Harty himself, however was an Edwardian composer who followed the

example of contemporaries like Holst and Vaughan Williams and incorporated folk

music into these pieces to make them practically the only Irish sounding works

in the entire Classsical repertoire.

I think you will love this music too!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5262537-1389015812-3185.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4410030-1364138925-5809.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-8357595-1460038536-5807.jpeg.jpg)