Our 2022 year-end post is likely the last blog post for me – at least for the foreseeable future.

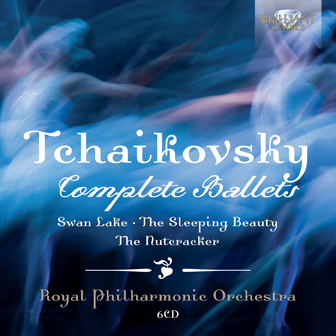

As I stated in September, nearly 12 years into this experiment, I have concluded that it is time for me to take a step back. In that vein, our montage no. 400 featuring Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty will be my last in our Friday series.

When we began this experiment in 2011, few of us could see a fundamental change in the delivery of music, with the near-dominance of subscription streaming music services and digital media purchases rather than hard media like CDs and the boutique vinyl business. This is true in popular music, as it is in classical/concert music and opera.

I began bundling music in the form of podcasts as a way of filling a gap I perceived, that was created in Canada with dependable sources of on-demand music leaving terrestrial airwaves. Little did we know that the music listening public would make the transition so easily to newfangled media.

In short, what I do isn’t really required anymore, and the time I once thought I’d have in semi-retirement to dedicate to this venture is more scarce than I imagined it would be.

The future of “For Your Listening Pleasure”

I must remind you that our Internet Archive has the bulk of our music shares readily available to listen to (with their built-in player) or for download. As long as that service is around, that music will be there for all to enjoy.

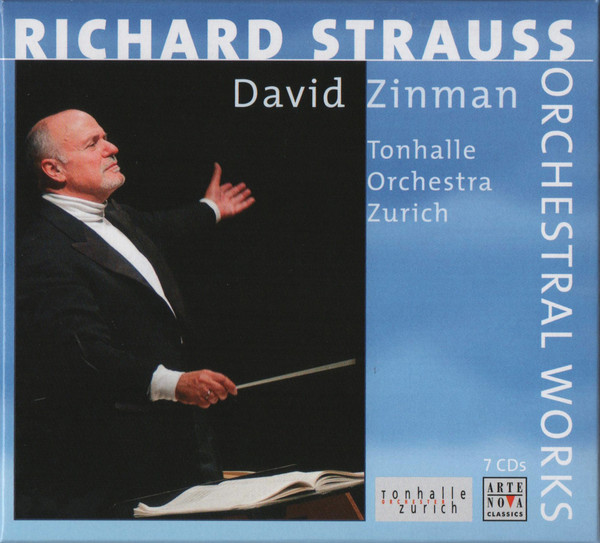

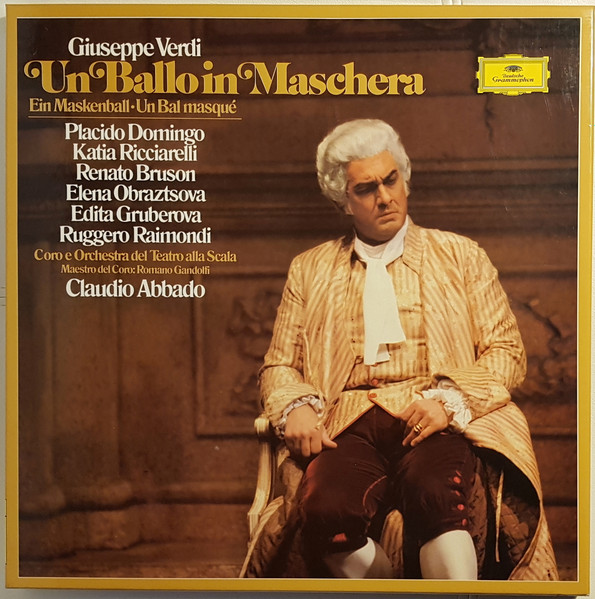

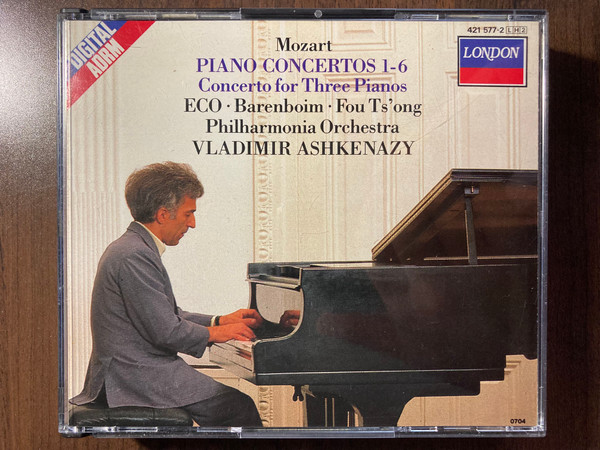

At this time, I still have a good number of past Tuesday shares and Operas that have not yet been posted on the Podcasting Channel, and in the spirit of curating our archived content I plan to do just that – post them in slow time as I curate the archive. Don't be surprised if the odd A la Carte post pops up every now and then as part of that exercise.

As a service to all of my listeners, I will maintain past episodes currently active until the end of January, slowly reducing our footprint down to the “basic” (free of charge to me) 500 MB storage level – which amounts to 5 - 7 episodes. There will be a commensurate download limit, but if I post to the archive concurrently, that won’t be too much of an issue.

As I post newly curated material, I’ll pull out oldest montages. When I’m done with that, I’ll take stock of the activity om the podcast and decide what happens next.

Before I leave you to enjoy our annual YouTube playlist of goodies, I wanted one last time to thank you for joining me in this experiment. It was fun while it lasted!

Happy holidays and Happy 2023 to all!

Pierre