|

| This is my post from this week's Tuesday Blog. |

This week’s Cover 2 Cover post completes our month-long look at Mahler symphonies, and in particular the set composed between 1903 and 1906. After the Eighth and Seventh (on my podcast this past Friday), now the Sixth.

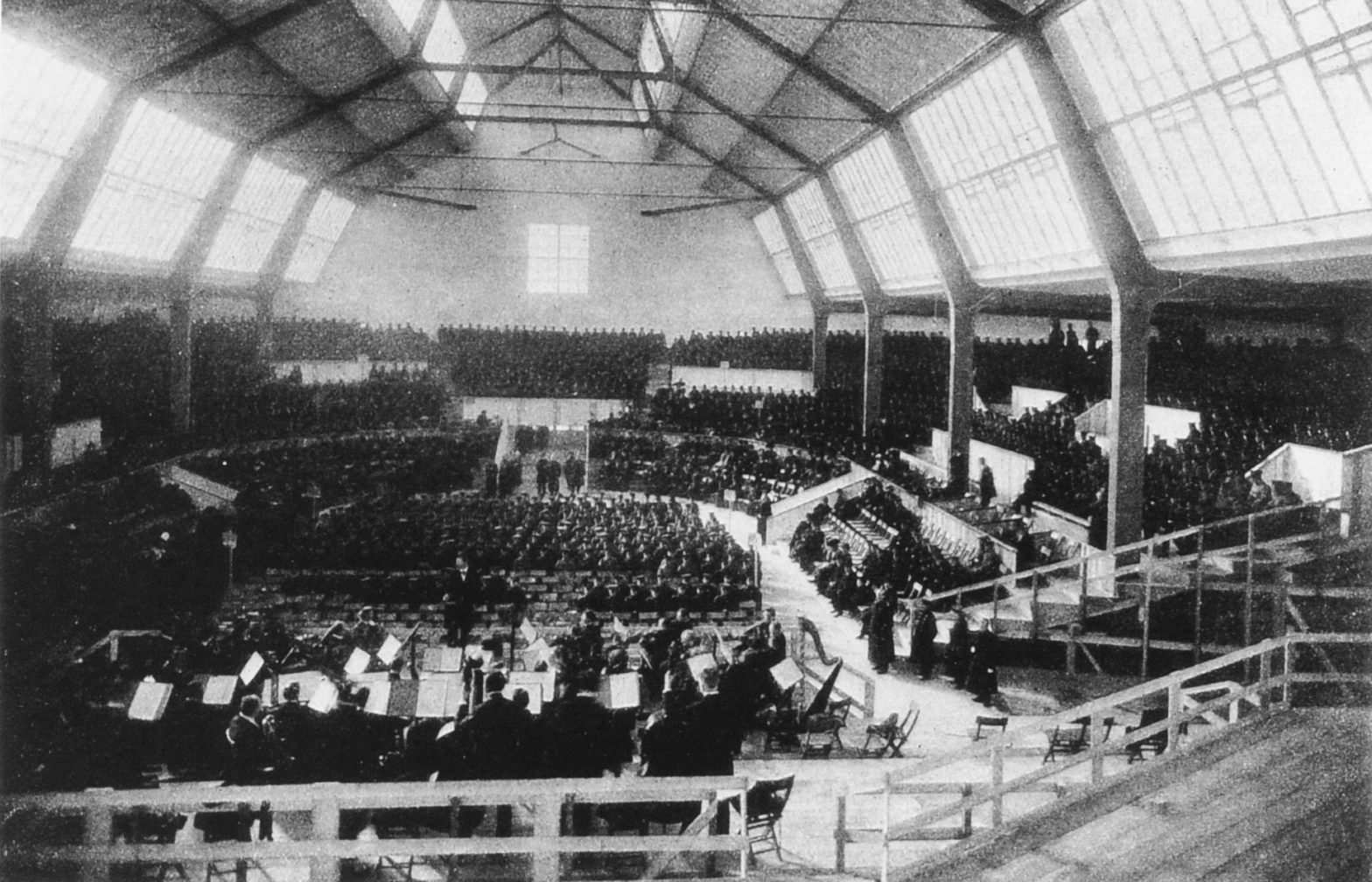

Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 is a symphony in four movements, composed in 1903 and 1904 (scoring repeatedly revised). Mahler conducted the work's first performance at the Saalbau concert hall in Essen on May 27, 1906. Mahler composed the symphony at what was apparently an exceptionally happy time in his life, as he had married Alma Schindler in 1902, and during the course of the work's composition his second daughter was born.

Both Alban Berg and Anton Webern praised the work when they first heard it. Berg expressed his opinion of the stature of this symphony in a 1908 letter to Webern: "Es gibt doch nur eine VI. trotz der Pastorale." (There is only one Sixth, the Pastoral notwithstanding.)

As I stated in past musings, Mahler’s trio of life-changing events in 1907 – presaged by the “three hammer blows” that mark the symphony’s finale help feed the myth behind the symphony’s subtitle “Tragic”. Mahler did not title the symphony when he composed it, or at its first performance or first publication. In his Gustav Mahler memoir, Bruno Walter claimed that "Mahler called [the work] his Tragic Symphony". Additionally, the programme for the first Vienna performance (January 4, 1907) refers to the work as "Sechste Sinfonie (Tragische)".

The sound of the hammer, which features in the last movement, was stipulated by Mahler to be "brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe)." The sound achieved in the premiere did not quite carry far enough from the stage, and indeed the problem of achieving the proper volume while still remaining dull in resonance remains a challenge to the modern orchestra. Various methods of producing the sound have involved a wooden mallet striking a wooden surface, a sledgehammer striking a wooden box, or a particularly large bass drum, or sometimes simultaneous use of more than one of these methods.

Conductor and friend of Mahler’s Bruno Walter found the piece too expressively dark for him to conduct, since it “ends in hopelessness and the dark night of the soul”. Late in his career, Pierre Boulez recorded the Mahler cycle for DGG and the cycle started with this recording of the Sixth, which garnered two Grand Prix du Disque in 1995 and 1996. The Sixth is the only Mahler symphony with a subtitle carrying an emotive adjective, in this case “Tragic”. As you would expect, Boulez eschews the tragedy, and to some that lessens the quality of his readi8ng. All agree, however, the Vienna Philharmonic as per usual plays splendidly.

We will also agree that, when it comes to Boulez and Mahler, you either love it or hate it. To generalize: the pro-Boulez camp appreciates Boulez’s ability to X-ray the score and bring every detail and voicing out in extremely high definition, his scrupulous adherence to Mahler’s tempo markings, as well as an unerringly taut sense of structure, while the anti-Boulez camp dislikes the chilly demeanor and emotional economy Boulez brings to his performances, at odds with the “true Mahlerian brand” of extravagance in expression.

A recording well-worth listening to.

Happy Listening

Gustav MAHLER (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 6 in A minor (Tragische, 1903-04)

Wiener Philharmoniker

Pierre Boulez, conducting

Deutsche Grammophon – 445 835-2

Studio, 1995

Internet Archive - https://archive.org/details/PierreBoulezConductsMahlerSymphonyNo.6

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3563770-1335438347.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3103204-1372966378-2183.jpeg.jpg)