As we showed on a graphic in the previous installment, not all

instruments are created equal, and not all instruments are showcased equally in

solo repertoire. Keyboard instruments like the piano have a bigger share of

that repertoire because they provide a greater range of tones.

Physics explains how instruments produce sounds – it’s all

about creating waves, and amplifying them. Sound waves are generated through

the transfer of a mechanical wave,

that is to say, how a string, or a surface can be made to vibrate either

through the action of striking it, or plucking it, or blowing in it.

More Power

To get from Point A to Point B, people choose many mode of

transportation, one that suits their needs. A bicycle is very economical to

ride, doesn’t require much space, and provided that you are (physically) up to

it can get you anywhere through any road.

But who doesn’t like a train? There’s something

awe-inspiring about a powerful locomotive, how it makes the ground shake and

the air move… All this to say that it’s in our collective DNA – we always

look for things that can be made to be more powerful, more awe-inspiring. It’s

true of music and of musical instruments.

Size matters! Physics also dictates that the size of the

physical source of a sound wave (a string’s length or thickness, the size of a

reed, the thickness of the skin on a drum) dictates vibration frequency, which

explains why a violin has four strings and a long fret. It stands to reason

that a large keyboard instrument can house many strings, thus support a larger

breadth of tones.

Keyboard instruments, the piano in particular, are the

results of innovations and evolution. The harpsichord,

which is really the grandfather of the piano, was designed to “pluck” strings,

and as such was limited in “dynamic range” – it doesn’t matter how “hard” or

how “softly” you hit the keyboard, the resulting sound is the same.

By “hammering” on strings rather than plucking them, the fortepiano provided this added dimension

of “dynamics”. Like the name suggests, this keyboard instrument has the ability

to play notes hard (forte) or softly

(piano). The last innovation is the

ability to further enhance the dynamics by “dampening” the vibration of the

string – this action, which is achieved by raising or lowering the instruments’

bottom surface through a pedal, takes us to the instrument we know recognize as

the “modern acoustic piano”.

Let’s think outside the box for a minute; simple wind

instruments – like a flute –create distinct notes through standing acoustic waves. A standing wave results in this case from acoustic waves bouncing off the ends of a pipe several thousand times a second

“beating” into each other until we get a unique “signature” wave. The resulting

note is dictated by that signature wave that is unique to the pipe (whose

characteristics change when a flautist changes how he blows in the flute, or

plugs holes with his fingers and instrument keys).

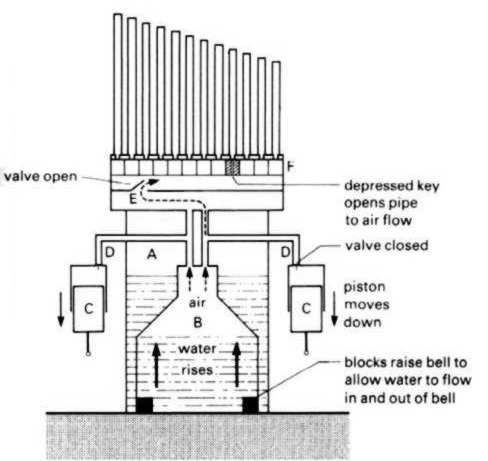

What if you engineered an instrument with several pipes,

tuned to specific pitches, and came up with a way to pick the pipes you want to

create the notes you want… That’s precisely what an organ does – it produces sound by driving pressurized air through

pipes selected using a keyboard. The organ's continuous supply of wind allows

it to sustain notes for as long as the corresponding keys are depressed, unlike

the piano whose sound begins to decay soon after a key is hit.

The potential for an organ to achieve epic scales is, well, huge!

The smallest portable pipe organs may have only one or two dozen

pipes and one keyboard (or manual);

the largest may have over 20,000 pipes and several manuals. They are installed in

churches, synagogues, concert halls, schools, and other public buildings

primarily because they are so large, require so much space and care that they

are not practical anywhere else.

From Ancient Greece to Gothic Churches

The origins of the pipe organ

can be traced back to the Hydraulis, literally

"water (driven) pipe (instrument)." It is attributed to Ctesibius of

Alexandria, an engineer of the 3rd century BC. The hydraulis was the world's

first keyboard instrument and was, in fact, the predecessor of the modern

organ.

Technical Diagram of Ctesibius; Hydraulis

The Hydraulis of Dion, Dion Archaeological Museum

Unlike the instrument of the Renaissance period, the ancient hydraulis was played by hand, the keys were balanced and could be played with a light touch, as is clear from the reference in a Latin poem by Claudian, who uses this very phrase (magna levi detrudens murmura tactu . . . intonet, “let him thunder forth as he presses out mighty roarings with a light touch”).

We can trace the origins of

the organ to the Ancient Greeks, however advances in

engineering over centuries culminate with the first documented permanent organ

installation, in Halberstadt, Germany in 1361. The Halberstadt organ was the

first instrument to use a chromatic key layout across its three manuals and

pedalboard, had twenty bellows operated by ten men, and the wind pressure was

so high that the player had to use the full strength of his arm to hold down a

key.

Now that’s power!

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the organ's

tonal colors became more varied. Organ builders fashioned stops that imitated

various instruments, such as the viola da gamba. The Baroque period is often

thought of as organ building's "golden age," as virtually every

important refinement was brought to a culminating art.

Overview of the Repertoire

As for the repertoire for the organ it is quite varied:

concert music, sacred music, secular music, popular music… In the early 20th

century, pipe organs were installed in theaters to accompany films during the

silent movie era!

Because organs have been used constantly over the centuries,

there are significant works for the pipe organ throughout the ages. However, in

my opinion, we can narrow things down to two distinct periods – the Baroque and

the period after 1865, with an emphasis on generation or two of French artists

that dominated the landscape at the turn of the 20th century.

Although most countries whose music falls into the Western

tradition have contributed to the organ repertoire, France and Germany in

particular have produced exceptionally large amounts of organ music.

German sacred organ music is dominated by the chorale, hymnal music of the Lutheran

faith. Composers such as Samuel Scheidt

and Heinrich Scheidemann wrote

chorale preludes, chorale fantasias, and chorale motets. Towards the end of the

Baroque era, the chorale prelude and the partita (or suite) became mixed, forming

the chorale partita. This genre was developed by Georg Böhm, Johann Pachelbel,

and Dieterich Buxtehude. The primary

type of free-form piece in this period was the praeludium, as exemplified in the works of Matthias Weckmann, Nicolaus

Bruhns, Böhm, and Buxtehude.

Johann

Sebastian Bach composed extensively for the organ (as well as the

keyboard), and his works are both secular (large-scale preludes and fugues) and

sacred (chorale-based works), dedicated to the organ or featuring the organ in

one of his many cantatas.

In France, very little secular organ music was composed

during the Baroque period; the written repertoire is almost exclusively

intended for liturgical use. The important names there were Jean Titelouze, François Couperin, and Nicolas

de Grigny.

Organ music was seldom written in the Classical era, as

composers preferred the piano with its ability to create dynamics. In Germany,

the six sonatas op. 65 of Felix

Mendelssohn (published 1845) marked the beginning of a renewed interest in

composing for the organ. Inspired by the work of renowned French organ builder

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, the French organist-composers César Franck, Alexandre

Guilmant and Charles-Marie Widor

led organ music into the symphonic realm. Guilmant and Widor were not only

great organists and composers, they were also great teachers, and among their

students and apprentices we count Louis

Vierne and Marcel Dupré who, in

turn, instructed Olivier Messiaen,

and the brother and sister tandem of Jehan

Alain and Marie-Claire Alain. Many of these organists were closely

associated with the many great church organs in France, from Notre-Dame-de-Paris to Saint Sulpice.

The Great Organ at Saint Sulpice (Paris), reconstructed by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll in 1862

The Great Organ at Saint Sulpice (Paris), reconstructed by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll in 1862

The development of symphonic organ music continued with

Vierne and

Charles Tournemire. Widor

and Vierne wrote large-scale, multi-movement works called

organ symphonies that exploited the full possibilities of the

symphonic organ.

Exploring the organ repertoire - Some Listener Guides

Listener Guide #7 - "Norddeutsche Orgelschule": A selection of works from the North-German organ school performed by Dutch organist Piet Kee: Sweelinck, Buxtehude ad J. S. Bach. (

ITYWLTMT Montage #217 - 11 March 2016)

Listener Guide #8 - "J.S. Bach - Ton Koopman - Organ Works": Dutch organist Ton Koopman performs some Toccatas and Fugues by J. S. Bach, including his well-known Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. (

Vinyl's Revenge #7 - 10 March 2015)

Listener Guide #9 - "French Organ Masterworks": A collection of French organ works from Late Romantic and Early Contemporary French organ composers: Franck, Dupre, Messiaen, Widor and Vierne. (

Once Upon the Internet #25 - 18 March 2014)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6456291-1452265242-2200.jpeg.jpg)